Antarctic Adventure

Two Mawrters head south to study sea-level rise.

What makes a great geologist? When Rachel Clark ’16 was an undergraduate student at Bryn Mawr, an acquaintance told her, “The best geologists see the most rocks.”

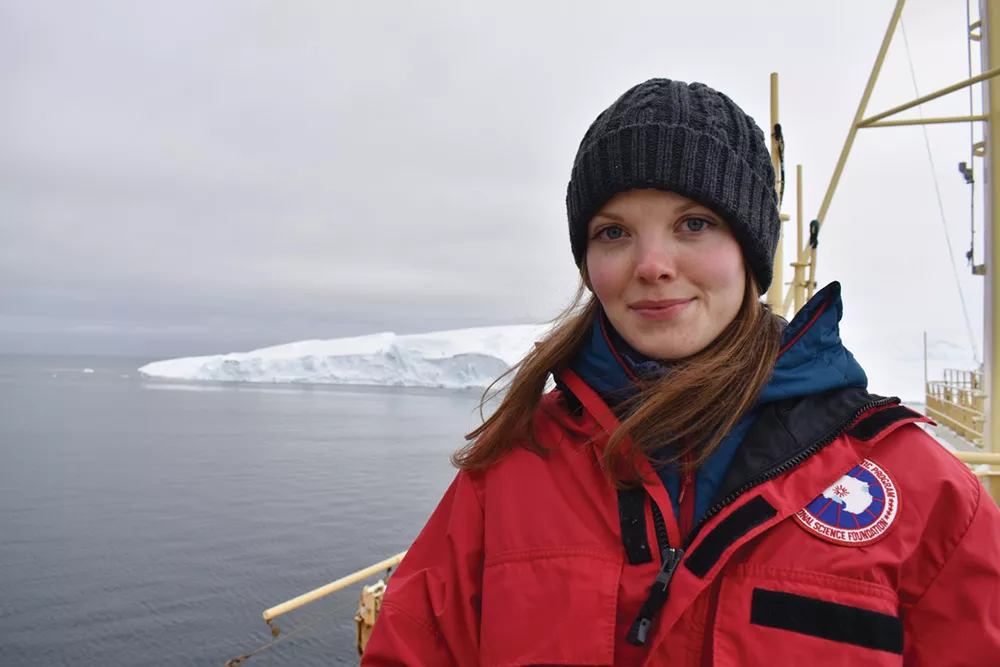

Since then, Clark has lived out that tongue-in-cheek advice by traveling to Death Valley, Joshua Tree National Park, and the Bahamas with Bryn Mawr’s geology department. She also completed a two-month research cruise to Antarctica earlier this year as a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Houston.

Clark knew she wanted to study geology even before arriving at Bryn Mawr. “I’m one of those people who’s strangely fascinated by rocks,” she explains. She looks back fondly on her time in college, where she found a home in the tightly knit geology department and took classes with as many professors as possible.

It was a Bryn Mawr connection that drew Clark, at least in part, to the University of Houston. Her academic advisor, Julia Wellner, is a member of the Bryn Mawr Class of 1992. In what Clark remembers as a fortuitous twist of fate, she contacted Wellner while considering graduate schools. The two shared not only an alma mater but also an interest in geological exploration. When Wellner mentioned the possibility of a research cruise to Antarctica, Clark was captivated.

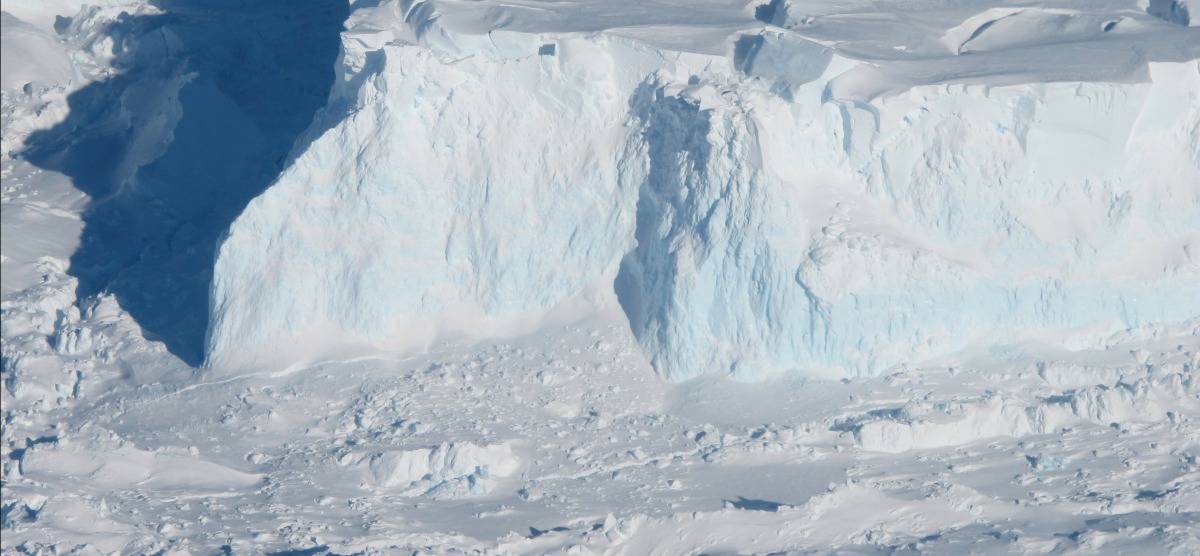

Wellner is the lead principal investigator on the Thwaites Offshore Research (THOR) project, sponsored jointly by the United States and the United Kingdom as part of a larger international collaboration. Little is known about the Thwaites Glacier (pictured), and THOR’s mission is to study the sediments found around it and map the nearby seafloor in an attempt to learn more about its recent history. For around 30 years, the vast glacier—currently similar in size to Florida—has been melting at an alarming rate. By studying the glacier’s history and oceanographic factors causing its instability, researchers will ultimately be able to better predict the rate and shape of future ice loss.

One way to learn about a glacier is to study the sediment it leaves behind. As glaciers move over the earth, they scrape up various minerals and then deposit them back into the ocean. By analyzing these preserved layers of sediment, scientists can learn about the environment at various periods of the glacier’s history. “The sediment is like pages in a book,” Clark explains. “As you go deeper and deeper, you’re turning the pages and learning more about the history in that location where the sediment is from.”

As part of the THOR team, Clark lived on an icebreaker ship from January to March 2019. Working in fast-paced, 12-hour shifts, she collected and archived sediment cores, which are cross-sections of these historical sediment layers. Now back in Houston, Clark will continue this work, measuring radioactive lead and carbon in the samples in order to date them and understand the timing of recent glacial retreat.

Working on the icebreaker exposed Clark to a diverse coalition of scientists and methodologies and showed her the importance of sharing research, as each discipline enriched the others. She says that she looks forward to seeing how the results of her research can be integrated with the results of other scientists.

Clark’s two months at sea were a journey that oscillated between the “wild” and the “boring.” Long stretches of downtime with few distractions—there was no internet connection on board—were interspersed with unforgettable moments, like seeing an island covered with odd specks that turned out to be thousands of tiny penguins. Sleeping in a cabin bunk and gaining sea legs was a small price to pay for the adventure.

Published on: 11/19/2019