Bryn Mawr, the Bauhaus, and Breuer

In 1936, modernist architect Marcel Breuer designed a suite of bedroom furniture for Rhoads Hall. This unlikely match was the subject of a recent student-curated exhibition.

When I moved into my first dorm room at Bryn Mawr, I felt as if I was entering history. I could almost feel the presence of previous students who had lived in that very same room on the third floor of Brecon. When I packed up my last dorm room in Denbigh last spring, I realized I now understand the history of this place much more deeply than I ever would have imagined.

As part of a requirement for my museum studies minor, in the spring semester of my sophomore year, I pursued an experiential learning opportunity in Special Collections where I researched the furniture and design history of the College and even curated an exhibition of my own.

Carrie Robbins, the curator for art and artifacts, suggested that I organize an exhibition on Marcel Breuer, the Bauhaus architect who designed the bedroom furniture for Rhoads in 1936. This exhibit would coincide with the 2019 centennial celebration of the Bauhaus School. Art and design museums around the world were honoring this anniversary with exhibitions on the legacy of the Bauhaus—and Bryn Mawr was no exception.

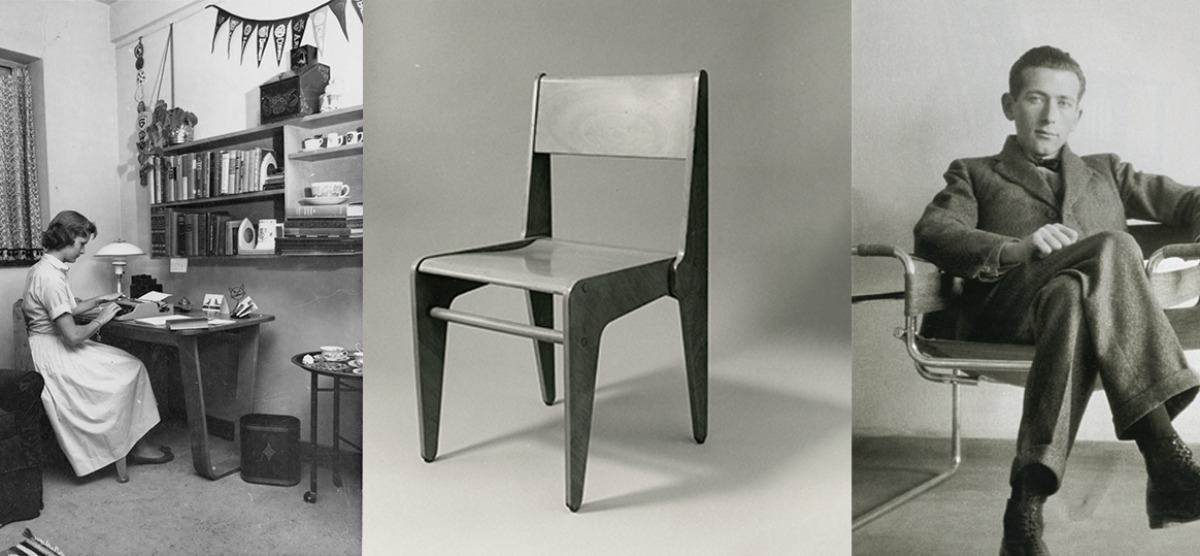

Upon encountering Breuer’s furniture for Rhoads—a set consisting of a chair, desk, bookshelf, and mirror—I was honestly underwhelmed; it looked like regular dorm furniture. Once I began learning about it, I realized that the simplicity of this set was exactly what made it so extraordinary.

Bauhaus and Beyond

The story of Breuer’s furnishing of Rhoads is a poignant reminder of the changing form of Bryn Mawr’s campus and a tangible example of how Bryn Mawr’s history is intertwined with the greater community. The furniture for Rhoads marked an important moment in Breuer’s artistic oeuvre and a significant shift in the development of modern furniture. It also affected the generations of Mawrters who lived in Rhoads with the furniture for almost 60 years.

My research began with the renowned German design school, the Bauhaus. Founded by Walter Gropius in 1919, the Bauhaus embodied the forward-thinking spirit of Weimar Germany. Ornate detail work was rejected in favor of simplified use of color, line, and materials.

Breuer, born in 1902, was a student at the Bauhaus and was considered such a visionary that he was invited back to be the head of the carpentry shop. It was there that he designed his first famous chair: the Model B3 “Wassily” Chair. Breuer’s revolutionary use of tubular steel construction with this chair let people feel as though they were “sitting on a cloud.”

The rise of the Nazis brought an end to the Bauhaus—newly deemed a bastion of “degenerate art”—in 1933. The students and staff, many of whom were of Jewish descent, including Breuer, fled Germany and resettled around the world, spreading the design principles of the Bauhaus. Breuer and his mentor, Gropius, settled in England. My own great-grandparents had also fled Europe because of their Jewishness in the early 20th century, and learning this history of the Bauhaus helped me feel a connection with Breuer.

Each leg of Breuer’s journey influenced his design, as he learned and experimented with different materials. While working for the Isokon architecture firm in London, he began translating his earlier designs from tubular steel into plywood, creating the award-winning Isokon Long Chair, as well as other furniture that explored the possibilities of plywood.

Breuer at Bryn Mawr

Breuer’s experiments in plywood would accompany him to Bryn Mawr. After only two years in England, Breuer and Gropius relocated again to America in 1937, where they both accepted teaching positions at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. That same year, Breuer accepted his first design commission in the U.S., the dorm furniture for Rhoads Hall.

Rhoads was built in the Collegiate Gothic style, complete with ornate stone detailing, magnificent wrought-iron windows, and the overall feel of a castle. This new dorm fit right into the campus, meshing well with nearby Goodhart Hall and Old Library. Why, then, was such modernist furniture designed for Rhoads?

In the exhibition, I asked: How is it that the plain, rectilinear Park Science building and romantic, castle-like Rhoads were built in the same year (1937)? And furthermore, isn’t it odd that the furniture for Rhoads, with its modernist simplicity, seems better suited for the interior of Park than Rhoads? These architectural and design juxtapositions reveal an ongoing identity crisis; the College wanted to maintain its Collegiate Gothic image but at the same time be relevant and contemporary.

The furnishing committee for Rhoads—composed of the director of halls, a few involved alumnae, and two undergraduate representatives—began their search for furniture in department stores, looking for a readymade set, but to no avail. They then had two sets prototyped. The first was discarded because, in the words of the committee, it “had no eyelashes.” The second set was Breuer’s design.

Breuer’s chair for Rhoads is of a cutout design: the sides of the chair punched out like puzzle pieces from a sheet of plywood. The curved leg of the Bryn Mawr desk is a testament to the strength of plywood. Whereas normal wood would split and splinter along a bend, plywood can be bent in any form. Overall, you can see the Bauhaus influence in the simplicity of the set. There are no frills or hard edges. Every form has a function.

An Unlikely Alliance

How is it that Marcel Breuer even came under consideration for a commission at Bryn Mawr College? The Bryn Mawr alumnae network, of course. One of the alumnae serving on the furnishing committee was Elizabeth Moore Cameron (née Elizabeth Ripley Moore), class of 1928. Her sister, Dorothea May Moore, class of 1915, was teaching at Harvard Medical School while Breuer was at the university, and Moore’s correspondence with her sister makes clear that she was the point of introduction between the designer and the Bryn Mawr furnishing committee.

In Breuer’s first proposal for the set, he designed a highly unconventional chair whose seat and back were made up entirely of wooden dowels. He attempted to persuade the committee to take a chance on this new kind of chair, writing: “The chair will seem a little strange at first, as its technique and form are quite new.” He suggested that students could personalize their chairs by braiding a thin rope between the rungs. When the committee received the prototype, it was quickly rejected as too uncomfortable; they wanted a chair that would be comfortable without any added cushioning. Breuer then replaced the rungs with a solid seat and back. It is ironic that many alumnae described to me how uncomfortable the chairs were; indeed, photographs of the chairs in use frequently include pillows!

Breuer’s initial proposal also included a sketch for a bookshelf that hung on the wall, instead of standing on the ground. The alumnae of the furnishing committee wrote that they were “delighted with your [Breuer’s] suggestion about bookcases, but we have been unable to convert the undergraduates who are vigorously opposed to having bookshelves they cannot move around.” Breuer assured them that they would appreciate the extra floor space that these hanging shelves would provide in such small rooms. He suggested that the bookshelves hang on metal hooks to allow them to be hung up in any part of the room. The committee agreed to this, and Breuer’s proposed idea prevailed. For any alumnae reading this who lived with Breuer’s furniture in Rhoads but did not have the luxury of moving their bookshelf around the room, this is likely because, as the furniture aged and the metal hanging mechanisms broke, college facilities staff bolted the bookshelves directly to the wall.

In Situ

Ultimately, Bryn Mawr commissioned 120 sets of Breuer’s plywood furniture for both wings of Rhoads. When the dorm opened in 1939, his furniture was met with praise by the alumnae and students, even those who had had misgivings, calling it “heavenly” in this very publication, the Alumnae Bulletin.

Breuer’s furniture was in use in Rhoads from 1939 until the hall’s renovation in 1999. For 60 years, Mawrters lived with and put their own spin on Breuer’s design work. I find it amazing that, despite how much everything else changes, the furniture looks at home in photographs of Rhoads rooms. His timeless designs accommodate the delicate tea sets of the 1940s as well as the electric water boilers of the 1980s.

By the late 1990s, the furniture was beginning to show signs of age. As a piece would fall into disrepair, Facilities staff would remove it from the dorm room, place it in storage, and replace it with a new readymade or modular piece of furniture.

Dispersing the Collection

When the hall was renovated in 1999, all of the furniture was replaced. What to do with the remaining sets of furniture? Even after 60 years of use, from the 120 original commissioned suites there remained 103 desks, 113 bookshelves, 57 chairs, 86 dressers, and 21 mirrors. It was decided that two sets would remain intact in Rhoads as “preserved rooms,” and one more would live in Special Collections. Letters were sent out to art and design museums in Europe and the U.S. offering donations of full sets of the Breuer furniture, which is why they now form part of the collections of the Harvard Art Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Bauhaus Museum, among others.

Although this would violate current policy, Bryn Mawr’s Special Collections’ Collections Committee decided to sell the remaining furniture at a 1999 Reunion Weekend sale. Intentionally priced below its market value to encourage maximal sales, 140 of Breuer’s pieces were sold at that sale. Furniture bought that weekend continues to circulate in secondary markets; single items sell for thousands of dollars (in 2012, a single Rhoads chair sold for $12,500). As a result of this, Breuer’s Bryn Mawr furniture is now all over the globe, held in collections or used in art lovers’ homes.

Breuer’s Legacy Lives On

Today, the “preserved rooms” in Rhoads still contain Breuer’s furniture and are lived in by students. In those rooms, the original desk, chest, and bookshelf remain in situ, but the chairs and mirrors have been replaced. It pains me that there is no plaque in those rooms to inform students of the furniture’s history and value. I know I was rough on my dorm furniture; I definitely would have wanted to be aware that it was worth thousands of dollars and had art historical importance!

In the short timeframe that I was researching this project, many of the students who lived in Rhoads seemed to have no idea or interest in who Breuer was. One fellow history of art major, however, had intentionally selected a Breuer room, and told me that she took special care not to further damage the furniture, saying, “I even got coasters so I wouldn’t leave any water stains!”

Although Breuer’s furniture is no longer in wide use at Bryn Mawr, it lives on in the hearts of the hundreds of alumnae who lived with it, in the museums where it is on display around the world, and sometimes at the College where students continue to live with it. Just as Breuer’s furniture was celebrated at Bryn Mawr during the College’s centennial in 1985 and for the Bauhaus’s centennial in 2019, I hope it will be celebrated at the centennial of Breuer’s furnishing of Rhoads in 2037.

Rachel Grand ’21 double-majored in history of art and fine arts with a minor in museum studies. While at Bryn Mawr, she participated in the 360 class that organized the exhibition ReconTEXTILEize: Byzantine Textiles from Late Antiquity to the Present (2019) and presented her own exhibition, Jewish in the Bi-Co, of photographic portraits of Jewish-identifying students with the Pensby Center (2021).

Published on: 02/23/2022