Fake News

A master’s student unravels the provenance of a 15th-century manuscript.

The assignment was open-ended: select a manuscript from Special Collections’ holdings of rare books and manuscripts and engage the material text in some way.

The project was the final for Forming the Classics: From Papyrus to Print, co-taught by Classics Professor Catherine Conybeare and Director of Special Collections Eric Pumroy. The class focuses on methods of textual history research, including paleography (the study of handwriting), book production, and manuscript transmission.

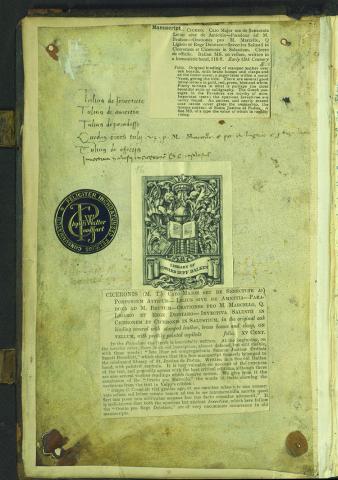

For his investigation Joshua Shaw, a master’s degree student in classics, focused on the provenance of Manuscript #4 (M4), a compilation of writings by Cicero—the subject of Shaw’s thesis research—and other Roman writers.

Thought to have been meticulously copied by scribes in the 15th century, M4 is on loan to Special Collections from the Gordan family collection.

“Provenance is fundamental to our understanding of a manuscript,” says Shaw. “This is often the first principle on which many other important observations rest. If you can find out when and where it came from, then you can make sense of many of the other pieces.”

M4’s history seemed impeccable: it was sold up to six times between 1849 and the 1920s. In the late 19th century, it was brought to the William Fitzgerald Library at Cambridge University, where a librarian determined that it came from the archive at a famed Italian monastery, which had been a major center for the training of church scribes. And that attribution made sense: M4 is clearly written by a number of different hands—the telltale mark of an army of scribes-in-training. And an inscription on the inside cover declared that the book was from the scribal school and monastery in Padua, Italy—neatly confirmed by an extant 1453 catalog.

Its provenance gave the manuscript the sort of historic flare that excites collectors—and prices. Yet Shaw was troubled by later inscriptions, found on the inside front cover. Made by prior owners, these inscriptions served to confirm possession or affix authenticating provenance information. On close examination, Shaw determined that some had been erased and chemically altered—a characteristic practice of 19th-century forgers.

But, ironically, the very process of chemical alteration that forgers used to mask provenance information has allowed modern technology to recover it: the chemicals used in the erasure process react with ancient ink and leave a distinctive signature detectable by ultraviolet photographic techniques. What was state-of-the-art forgery technology in the 19th century is now the con’s greatest foil.

Working with Special Collections’ photogrammetry technology, Shaw captured images of the manuscript that, in post-processing, revealed a startling secret: at some point in the 19th century, key provenance information about the book had been erased.

With UV testing, Shaw recovered accession numbers that had been chemically scrubbed. And, contrary to the information inscribed in M4’s inside cover, what emerged did not correspond to any accession number in the 1453 Padua library catalog. M4’s official accession history was a lie.

But was the entire book a fraud? Or was it simply that the provenance had been faked to increase its value?

Find out the end of the story here.

Published on: 09/23/2019