First Times Two

How one alumna set her sights on new heights for women.

“I’m not going to have it said there’s any place I can’t go. If you can’t do it, it’s something you’ve got to do.”— Jeannette Ridlon Piccard, Class of 1918, quoted in Notable American Women, A Biographical Dictionary (Harvard University Press, 2004)

Jeannette Ridlon Piccard graduated from Bryn Mawr College two years before American women gained the right to vote nationwide. In subsequent decades, her courage and perseverance would take her up into the stratosphere in 1934—making her the first woman to go into space—and, 40 years later, to ordination as the first woman priest in the Episcopal Church.

I live in the Twin Cities of Minnesota, as did Jeannette during the last 45 years of her life, and this intelligent, ambitious Bryn Mawrter caught my attention in the 1970s. At that time, I was editing a massive reference book, Women’s History Sources: A Guide to Archives and Manuscript Collections in the United States (1979), as the field of women’s history was gaining traction. I had access to a range of primary sources—letters, personal papers, interviews, videos, and news articles— that documented Jeannette’s extraordinary life. She was a pioneer who broke barriers and showed what women can achieve.

AMBITIOUS ASPIRATIONS AS A CHILD

One of nine children, Jeannette Ridlon was born in Chicago in 1895. Her father was an orthopedic surgeon who cofounded the American Orthopaedic Association and served as its president. Jeannette recalled knowing that she wanted to be a priest when she was just 11 years old, after attending Episcopal Church services with a neighbor. As she told an interviewer from The New York Times in 1972, “My mother came into my room one night, sat down beside my bed and asked what I wanted to be when I grew up. When I said I wanted to be a priest, poor darling, she burst into tears and ran out of the room. That was the only time I saw my Victorian mother run.”

“My mother came into my room one night, sat down beside my bed and asked what I wanted to be when I grew up. When I said I wanted to be a priest, poor darling, she burst into tears and ran out of the room. That was the only time I saw my Victorian mother run.”

Jeannette attended Miss Shipley’s School in Bryn Mawr as a boarding student and then enrolled at Bryn Mawr College. When President M. Carey Thomas learned that Jeannette wanted to be an Episcopal priest, she smiled and nodded: “I’m sure, my dear, that by the time you graduate that will be entirely possible” (Notable American Women, 2004).

In 1916, Jeannette wrote a 14-page assignment at Bryn Mawr titled, “Should Women Be Admitted to the Priesthood of the Anglican Church?” There she argued, “In the study of history we note that as civilization increases, the status of women becomes more nearly equal to man … Today, woman has almost obtained equality with men. In some nations women may vote and hold civil office equally with men. All but one profession is now open to women: That is the Church.” She went on to state that educated women are equal to men, that their morality is “equal if not superior,” and that women live longer and are better at “bearing suffering and privation”—qualities she would demonstrate in her own adult life as she faced down gender-based barriers.

BUT FIRST, PIONEERING ACHIEVEMENTS IN HIGH-ALTITUDE BALLOONING

After graduating from Bryn Mawr, Jeannette studied organic chemistry at the University of Chicago under Swiss chemistry professor Jean Felix Piccard. In a story she wrote later for Reader’s Digest, found in her personal papers at the Library of Congress, in spring 1919 she asked her father, “If I let him, Jean Piccard will ask me to marry him. Shall I let him?” Dr. Ridlon replied, “If you believe that there is no other man in the world like him—and, if you are ready to go with him anywhere in the world— then yes, otherwise no.” “You go where the wind goes. You feel like part of the air. You almost feel like part of eternity.”

“You go where the wind goes. You feel like part of the air. You almost feel like part of eternity.”

Jeannette and Jean married after she received her master’s degree, and the couple moved to Switzerland, where Jean assumed a position as head of the chemistry department at the University of Lausanne. They lived in Lausanne for seven years and had three sons: John Auguste, Paul Jules, and Donald Louis.

In 1926, the Piccards returned to the U.S. so that Jean could teach organic chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Flight was still in its infancy: Charles Lindbergh would take his solo flight from New York to Paris in May 1927. Jean and his twin brother, Auguste, who was living in Europe, corresponded extensively as they worked to design and construct an experimental high-altitude balloon and pressurized gondola. (In 1931, Auguste and his colleague Paul Kipfer ascended in a hydrogen balloon from Augsburg, Germany, up 51,775 feet—becoming the first human beings to enter the stratosphere.)

High-altitude ballooning was quite dangerous: The hydrogen lifting the balloon was extremely flammable, and human lungs cannot function alone above 40,000 feet.

When Jean began preparing to take his own balloon up into the stratosphere, Jeannette decided to become the first woman licensed as a balloon pilot by studying with an experienced pilot. Her plan was to fly the balloon from its airtight, pressurized gondola while Jean collected data on the effect of cosmic rays in the upper air, where they are not altered by the earth’s atmosphere. Henry Ford himself offered them the use of his airfield and hangar at the Ford Airport in Dearborn, Michigan. Ford brought Orville Wright to observe one of Jeannette’s training flights in 1933, and on June 16, 1934, Jeannette made her first solo balloon flight into the atmosphere.

In the months leading up the Piccards’ flight, planned for fall 1934, they had difficulty finding sponsors. Goodyear and Dow Chemical turned them down. As Jeannette later said in a 1980 video for the Minnesota Living History Series, the couple appealed to the National Geographic Society, but the Society “would have nothing to do with sending a woman—a mother—in a balloon into danger.” Eventually, the Grigsby-Grunow Radio Company and the Detroit Aero Club and People’s Outfitting Company became sponsors.

On October 23, 1934, the Piccards took off from Dearborn at 6:51 a.m., assisted by a 30-man ground crew and watched by 45,000 spectators, including their three sons. When fully inflated, their Century of Progress balloon was 15 stories tall. Jeannette piloted the balloon from the gondola, which carried 168 Geiger counters for researching cosmic rays, as well as liquid oxygen and the family’s pet turtle.

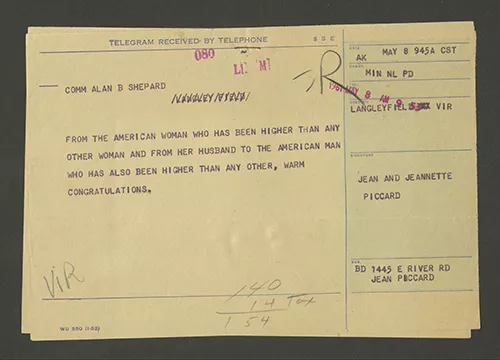

Jeannette and Jean achieved 57,579 feet or nearly 11 miles up, traveling for eight hours over Lake Erie with Jeannette steering through clouds, until they landed 300 miles away near Cadiz, Ohio. The New York Times described their feat as “the first such flight made in the United States in which a balloon remained under control for the entire flight” and “the first successful stratospheric flight made through a layer of clouds.” Today, the Piccard Gondola is permanently exhibited in the Transportation Gallery of the Museum of Science + Industry in Chicago.

The significance of the Piccards’ achievements was not lost on their descendants. The fall 1984 Bryn Mawr Alumnae Bulletin featured an interview with granddaughter Elizabeth Piccard ’79, who said, “They really didn’t know what would happen when they got up there. …They were making scientific history.” As grandson Dick Piccard, a professor of physics and astronomy at Ohio University, shared in an email, “Cosmic rays were in those days still quite mysterious and seemed potentially useful for learning parts of physics and astronomy that were not otherwise accessible to experimentation. Geiger counters were the tool of choice. …Supporting the weight of all that apparatus and shielding [lead shielding on the outside of the gondola] arguably prevented the flight from reaching an even higher altitude.”

Jeannette and Jean helped lay the groundwork for human space flight with their 1934 success. Moreover, Jeannette set the women’s world record for altitude—a distinction she held for 29 years until the Soviet Union’s Valentina Tereshkova orbited Earth and became the second woman in space. Years later, Jeannette’s son Don Piccard met Tereshkova at an international aeronautics conference; when he introduced himself, Tereshkova replied, “I know very well who your mother is. I am honored for her greeting and send her all my love.”

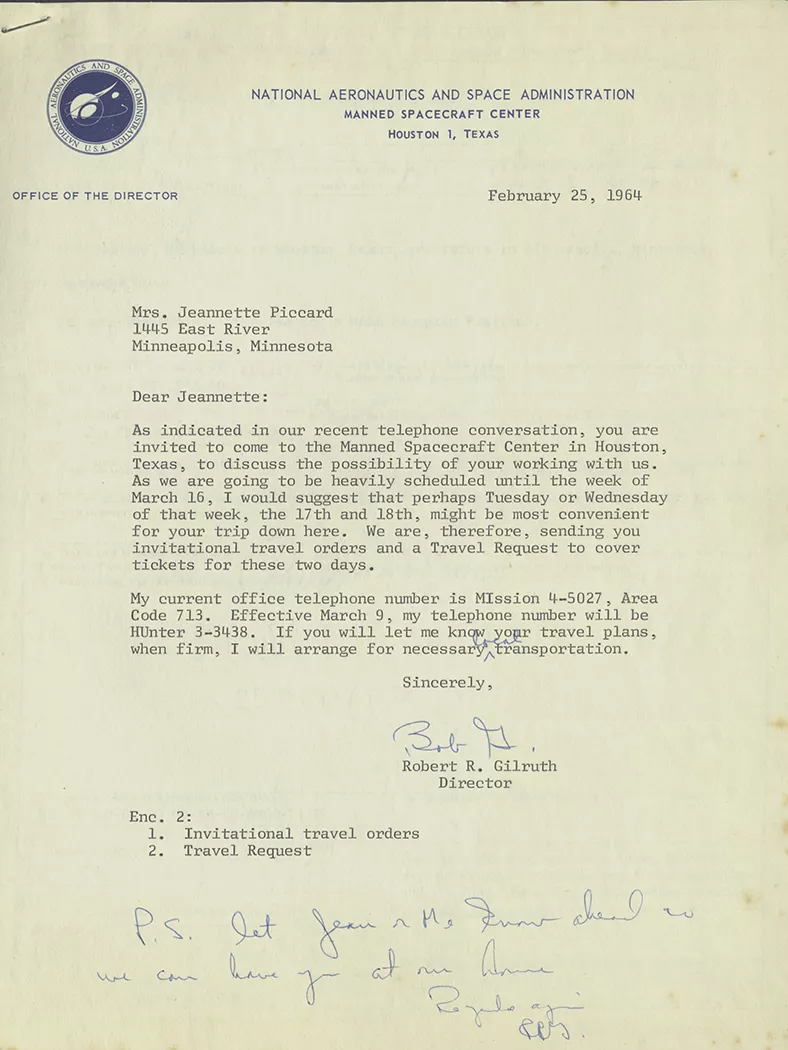

Jeannette and Jean toured the country for nearly two years, delivering lectures about their trip. John Akerman, an aeronautics professor at the University of Minnesota, invited Jean to teach aeronautical engineering there in 1936. The couple settled in Minneapolis and Jeannette earned her Ph.D. in education at the University of Minnesota in 1942. After Jean died in 1963, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) hired Jeannette as a publicity consultant, a job she held until 1970.

PURSUING HER LONG-DEFERRED DREAM

For more than 60 years, Jeannette had longed to become an Episcopal priest, as church was where she “felt filled with a sense of peace and well-being” (Betsy Covington Smith, Breakthrough: Women in Religion, 1978). In 1965, she met The Reverend Denzil Carty of St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, a predominantly Black parish in St. Paul, Minnesota. With his encouragement, Jeannette applied to become a lay reader, but Episcopal law stated that only “godly men” could read. Jeannette wrote a motion proposing a change in canon law, which passed at the General Convention of the Whole Church in 1967. In 1970, when the Church allowed women to become deacons, Jeannette studied Church history, liturgy, and theology and was ordained as a deacon, serving at St. Philip’s. According to granddaughter Elizabeth Piccard, this parish was the only place where Jeannette felt truly accepted because its members had experienced discrimination—and they understood her struggle to become a woman priest.

In 1972, at age 77, Jeannette spent a year studying at The General Theological Seminary in New York City, then returned to St. Paul. On July 29, 1974, Jeannette’s childhood dream came true at the Church of the Advocate, a Black church in North Philadelphia led by The Reverend Paul Washington, a civil rights advocate. Piccard and 10 other women deacons were ordained by three retired bishops; Jeannette, the oldest at age 79, was first to be ordained. Surrounded by her three sons and Rev. Denzil Carty, Jeannette knelt at Bishop Daniel Corrigan’s feet as he held her head in his hands and spoke the words making her the first female priest in the nearly 200-year history of the Episcopal Church. More than 2,000 people and all the major national news outlets attended the service, which lasted more than three hours. In a videotaped tribute to his mother in 2004, Paul Piccard recounted, “The sense of the Holy Spirit in that place was nearly tangible.”

Commenting on the “speak now or forever hold your peace” portion of the ceremony, grandson Dick Piccard shared in an email, “I was struck by the fact that several of the younger priests who spoke out against the ordinations were quite emotionally involved. …Their whole masculine identity was being shattered by the existence of even one woman priest, much less 11 then and multitudes obviously to come. They certainly came across to me as feeling very threatened.”

Two weeks later, at an emergency meeting of the House of Bishops, Presiding Bishop John Maury Allin declared, “The ladies are not priests.” The women faced threats, harassment, and intense anger. The Rev. Dr. Suzanne Hiatt, a member of the group that came to be known as the Philadelphia 11, later said, “In retrospect, to have been ordinated ‘irregularly’ is the only way for women to have done it.” It took the Episcopal Church two more years to open the priesthood to women at the 1976 General Convention in Minneapolis.

Jeannette served as an Episcopal priest for seven years, until she was 86. Perhaps because of her age, she found she had a special gift for ministering to sick and lonely older people in St Paul’s nursing homes. As Jeannette said, “It was a great joy to be able to give the spiritual food we need for our health and well-being.”

Besides serving as associate rector to Father Denzil Carty of St. Philip’s Church, Jeannette was a hospital chaplain at St. Luke‘s Hospital (now United Hospital) in St. Paul. In 1977, Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York, awarded her an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree. She received many other honors, and on May 13, 1979, Jeannette returned to Bryn Mawr College to deliver the commencement address at her granddaughter Elizabeth’s graduation.

The Rev. Dr. Jeannette Ridlon Piccard died on May 17, 1981, in Minneapolis at the age of 86. She was inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame posthumously in 1998. A new documentary called The Philadelphia Eleven, released in the fall of this year, tells the story of Jeannette and the ten other women who bravely broke new ground for the Episcopal Church 50 years ago.

Published on: 11/20/2023