The French Connection

The City of Brotherly Love Meets the City of Lights

Philadelphia was founded by an Englishman and remained a colony of the British crown for a full century. But even from the beginning, there were French connections.

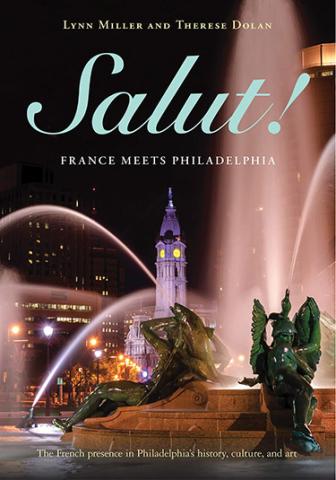

So argues Therese Dolan, M.A. ’74, Ph.D. ’79, in her latest book, Salut! France Meets Philadelphia. Co-authored with Lynn Miller, the book traces more than three centuries of French influence on the “City of Brotherly Love.”

That influence was there from the start. As it happens, William Penn’s father, in an effort to counter the lure of Quakerism, sent his son to France. The “cure” didn’t take; rather, the son fell in with Huguenots who preached religious tolerance. Through the Colonial period, that commitment would attract a cosmopolitan mix of religious nonconformists, including German Pietists and French Huguenots.

“With the coming of the American Revolution,” the authors write, “its leaders turned to France, Great Britain’s historical enemy.” That alliance saw an influx of Frenchmen—some commanding armies—to the city, and by the end of the 18th century, they composed an estimated 10 percent of its population.

Connections went the other way as well. William Penn wasn't the only Philadelphian to sojourn in France. During his two-year diplomatic mission, Benjamin Franklin negotiated a formal alliance between France and the rebel British colonies. And starting with Rembrandt Peale in the early 1800s, a long line of Philadelphians traveled to Paris to study at its famed ateliers. Following in Peale’s footsteps was a roster of distinguished artists, including Thomas Eakins, Mary Cassatt, Henry Ossawa Tanner, Edward Redfield, Robert Henri, and others.

Over the centuries, the French presence in Philadelphia has been historically small. Still, as the authors observe, “the contributions of comparatively few individuals have very much outweighed the rather small numbers of French and Francophone people who have immigrated to the Philadelphia region.”

Their disproportionate influence can be seen in many ways: the Parisian cast to the Champs-Elysées–inspired Benjamin Franklin Boulevard and the many Beaux-Arts buildings that line the Parkway; Logan Circle with its echoes of the Place de la Concorde; the collections of French art in the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Rodin Museum; and even the emergence of a world-class gastronomic scene in the late 20th century.

At times, the authors write, French influence has been obvious, sometimes oblique. “Over more than three centuries, the impact France and the French have made on Philadelphia has waxed and waned, as has the friendship between Philadelphians and the people of France. In this respect the Franco-Philadelphia story is something of a microcosm of that between France and

Published on: 07/02/2021