Mary Poppins Revisited

Practically Perfect in Every Way.

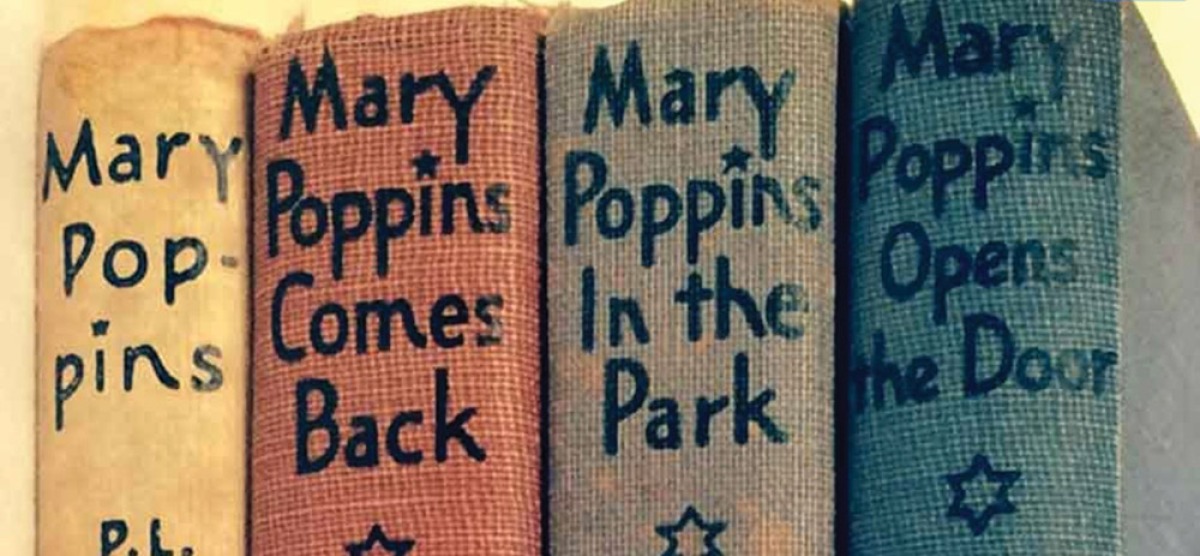

I spent Christmas 2018 on the sofa reading all three Mary Poppins books, which somehow had never been thrown away. In my editions, Mary Poppins and Mary Poppins Comes Back were in one volume, 1941, fourth printing. Mary Poppins Opens the Door was 1943, first printing. They’re in decidedly used condition, and Opens the Door has no spine, but they’re hardcover, and the yellowing paper is firm to the touch.

I, too, am on in years—three-quarters of a century from first reading, with insights and priorities that neither our culture nor I could have had as a child, during the war.

Mary Shepard, the illustrator, is the daughter of E. H. Shepard, who drew the Winnie-the-Pooh books and The Wind in the Willows. Mary’s line drawings have that sweet lilt of the head and lightness of motion that the jolly, grape-jelly musical film versions don’t capture at all. There is no treacle here—no spoonful of sugar, no mugging, no songs, no movie stars.

The first and final chapters of each book are about the amazing arrivals and departures of the magical governess at the middle-class Banks home in prewar London, where Mrs. Banks is clueless, and Mr. Banks goes to the city to make money. In the rest of the chapters, Mary Poppins whisks the Banks children—Jane, Michael, the twins, and in book two, Annabel—out for the afternoon. They have an astonishing, marvelous adventure, with people (or talking animals, or audiences of constellations, or romping statues) who tell the children that this wondrous event is created by the presence of Mary Poppins.

Impossible things go on: a riotous tea at a table on the ceiling; a circus of heavenly constellations where Mary Poppins dances—carefully— with the burning sun; flying over London while holding onto balloons with their names on them; or slogging through winter snow to a busy house where leaves and buds are being prepared for spring, to appear outdoors the next day. Use of the third dimension is imaginative and original, suggesting a provenance for Harry Potter.

At the end of the afternoon, Mary Poppins brings the children home to the nursery, where they question her excitedly. Unsmiling, she denies all, insulting and threatening them for suggesting what they have seen. They don’t dare ask anything further, but watching from their beds, they see, and reassure each other, that what happened was true: there’s always evidence for them to hold in their minds.

They deduce that they simply must have been inside that Royal Doulton china dish on the mantelpiece because Mary Poppins’ scarf is now pictured in the dish’s scene, where she had dropped it as she snatched the children away from the china kingdom. Or her smart new jacket now covers the nakedness of a marble statue in the park who, with his dolphin, had spent a joyful afternoon playing and reading with them. Or a bit of stardust briefly stuck to her ubiquitous parrot-head umbrella, before glimmering out.

Mary Poppins—who is never called anything else by the children, the household staff, or the narrator—is maybe meant to be some kind of god. She rules the children’s world with startling efficiency, and their hapless mother and the servants fear and respect her. She is rude and untruthful to the children, who love her because of her fascinating powers. She appears and disappears in mysterious ways—on the end of a kite or blown in by a breeze—and refuses to discuss it.

Vain and conceited, she preens at every windowpane but is kind to the least of society, who adore her: the matchman who draws on the sidewalk; the sooty chimney sweep; Robertson Ay, the dozing shoe-polisher. She is standoffish with her occasional magic relative that the little group visits, but like the children, they speak of her admiringly but don’t ask questions.

At the center of the second book, and of the third, are stunning chapters based on the idea that, like Mary Poppins, babies can talk to animals. The scene is the nursery, in the first book with the toddler twins, and baby Annabel, “The New One,” in the other. A starling, fledgling in tow, chats amiably with the babies and twits Mary Poppins, who shoos him off, flapping her apron as he squawks.

Annabel speaks poetically, describing her journey through a dark forest, musing that she is made of “earth and air, fire and water.” The starling listens affectionately and asks questions, but tells her—as he has told the twins earlier—that in a week they will no longer be able to understand him. They disagree and object, kicking furiously, and Mrs. Banks comes in to “therethere” them and murmur about teething pain. Enraged, they thrash more as the starling cackles, and Mary Poppins swipes at him.

He’s back on the windowsill in a week and tries to talk to them, but they merely coo and play contentedly with their toes. Knowing that he has lost them, he begins to weep. Mary Poppins mocks him.

And an aged reader on the sofa outside the book’s fourth wall, tattered book in hand, wonders, “How did I miss out on talking to birds? Or did I?”

Published on: 05/20/2020