Primary Sources

Investigating Incunables

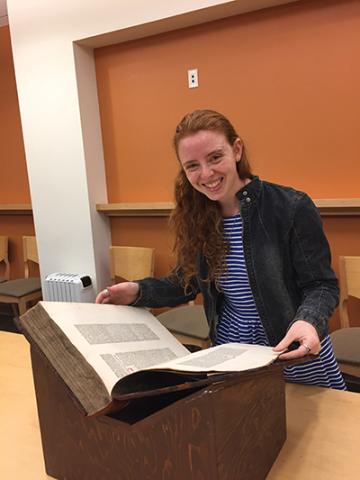

For a bibliophile like myself, there’s nothing quite like being surrounded by books. Still, stepping into Canaday’s Rare Book Room is an altogether different experience—like entering a church. But books aren’t sacred, even when they’re old. Bryn Mawr’s 15th-century incunables (or printed publications) were treasured, mistreated, and used by their owners for centuries, and behind every book, a story waits beyond the printed words. As a classics graduate student at Bryn Mawr, I’ve always loved stories. But classicists rarely work with “original” texts, which almost never survive. So, when offered a chance to work with physical books in Bryn Mawr’s Special Collections, I leapt at the opportunity.

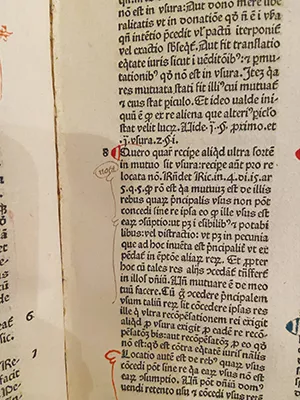

Incunables and provenance research were new to me, but I was quickly hooked. Marks of provenance—evidence of previous ownership—come in many forms: paper bookplates with detailed crests, scrawled inscriptions, or ink stamps. They may be pasted inside a book’s cover or buried in the text. Some are clear and others illegible, but each one contributes to the book’s history.

My job has been to record and photograph these provenance marks and date them wherever possible. Sometimes that’s as easy as a Google search to determine the lifespan of a bookplate owner. Other times, I had to hunt through digital sale records or brush up on my Latin abbreviations in hopes of deciphering an inscription. I have experienced successes, like the discovery of a 1911 auction catalogue that confirmed our 1482 copy of Claudian’s Opera was owned by the Huth family before its acquisition by the Earl of Cromer. And I also have mysteries yet to solve, like an ink symbol that I thought was Jesuit but haven’t been able to find anywhere. All this information goes into Bryn Mawr’s own records. But we’re looking beyond Bryn Mawr, too.

The British Library runs one of the largest provenance databases in the world—their Material Evidence in Incunabula (MEI) project collects provenance information and makes it accessible on an international scale. In November, along with Eric Pumroy (director of Special Collections) and Marianne Hansen (curator/academic liaison for Rare Books and Manuscripts), I took part in the British Library’s training program so that Bryn Mawr can add its incunables to the MEI database. This collaboration will increase the British Library’s data and open Bryn Mawr’s books up to outside researchers. Who knows what we may uncover together?

Of course, there’s more to the books than provenance. I’ve also gotten to participate in other projects, like a marginalia workshop run by University of Texas Professor Emeritus Marjorie Curry Woods as part of the Private Lives of Old Books exhibition displayed throughout fall 2021 in Canaday Library. Helping select the books used for the workshop allowed me to dig through the texts and make discoveries of my own, like a delightful “ha ha he” of laughter in the margin of a Plutarch manuscript.

A semester isn’t enough time to learn everything, but events like Professor Woods’ workshop and ongoing collaboration with the British Library will continue to provide opportunities to keep exploring books and all the different ways they can tell a story. For me, working with the incunables has confirmed something I’ve always suspected: books are not sacred, but they are a kind of magic.

Published on: 02/23/2022