Revisiting Superstorm Sandy

A new set of oral histories captures the stories behind a life-changing storm.

Ten years ago, Hurricane Sandy slammed ashore on the New Jersey coastline just north of Atlantic City. The storm, which had developed in the western Caribbean Sea, reached peak intensity in Cuba yet wreaked the most damage in the Northeastern United States.

Abigail Perkiss ’03, a history professor who lives in Philadelphia, got a sense of the storm’s impact when electrical outages caused her workplace, Kean University near Newark, N.J., to remain closed for 10 days.

At the time, Perkiss was finishing her first book, Making Good Neighbors: Civil Rights, Liberalism, and Integration in Postwar Philadelphia. When a friend at the regional oral history association asked if she knew of anyone doing oral history work on Hurricane Sandy, Perkiss realized this could be “an incredible opportunity to document a moment of history as it was still unfolding and to create a set of sources that people could use to understand the impact of Sandy and its broader historical context.”

Recognizing an opportunity to involve her students in the documenting process, Perkiss created a course around the oral history project. “It became bigger than the sum of its parts,” she says of what became a two-year longitudinal oral history project with more than 70 interviews conducted.

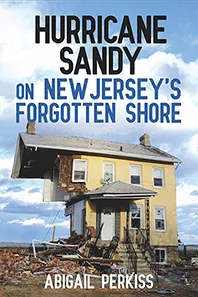

Hurricane Sandy on New Jersey’s Forgotten Shore (Cornell University Press) captures stories from residents, business owners, politicians, and policymakers. “We tried to get a holistic picture,” Perkiss says. “We spoke to some folks who lived further inland but ended up spearheading

volunteer efforts, and we also spoke to people who ran social service agencies. Many of them were both trying to rebuild their own lives and trying to respond to the needs of their communities at the same time.”

Among the themes that emerged from the many conversations was the shift in disaster preparedness that had taken place after 9/11 and was the norm by the time Sandy arrived. “That model privileged homeland security and military preparedness at the expense of environmental preparedness and public health preparedness,” Perkiss says.

It also shifted the emphasis to tourism so that, after the storm, the Atlantic coastline became the focus of the rebuilding efforts and the year-round residents felt marginalized and erased from the narrative.

The oral histories also offer perspective on the dilemmas around shoreline resilience—whether to rebuild the barrier islands or reinforce existing infrastructure. Most of what ended up happening, says Perkiss, was the latter, with houses raised to comply with new flood plain guidelines. “That totally remade the space,” she says, “making it harder for people with mobility issues, for example, to access the spaces.”

Perkiss says working on the project has informed her approach to her next book, where she plans to use oral history methodologies to write about the 1985 MOVE bombing, during which 61 residential homes in West Philadelphia were destroyed during a standoff between the MOVE organization and the police. Perkiss will specifically focus on how the journalists that covered the bombing curated the story and the public understanding of what was happening.

Through a partnership with Stockton University, the oral history interviews have been digitized and are accessible online.

Published on: 02/14/2023