A Woman of Science and Conscience

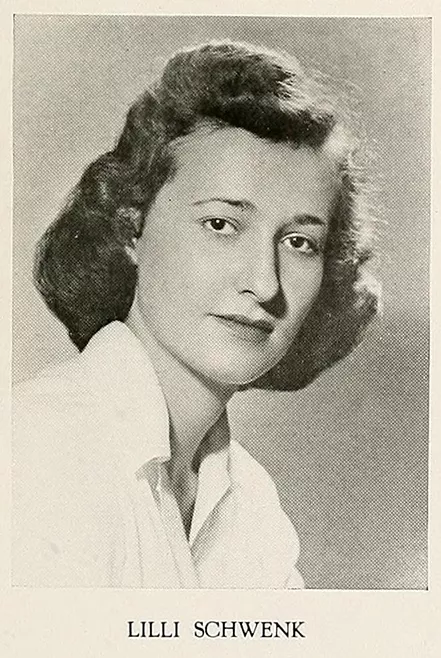

Class of 1942 alumna depicted in the summer blockbuster Oppenheimer.

Oppenheimer, the Christopher Nolan film on the making of the world’s first atomic bomb, features Lilli Schwenk Hornig ’42, a Czech-American chemist who worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II. Although many women played a role in the research project, Hornig is the only female scientist named in the film (played by Olivia Thirlby).

Hornig was born in the modern-day Czech Republic in 1921, moved to Berlin, Germany, with her family as a child, and then on to Montclair, N.J., after her Jewish father was threatened by the Nazis.

At Bryn Mawr, Hornig studied chemistry and lived in Rockefeller Hall for four years. She went on to earn her master’s in chemistry at Harvard University

In a 2011 interview for the Atomic Heritage Foundation, Hornig reflected on her time at Bryn Mawr and the transition to Harvard: “I went to Bryn Mawr and I had a marvelous, marvelous time; marvelous education, I think. And when it came to graduate school, there wasn’t much question I wanted to go to Harvard.”

Yet Hornig soon discovered pervasive sexism at Harvard. “[T]here wasn’t a ladies’ room in the building,” she recalled. “I had to go to another building to find the ladies’ room and I had to get a key for it . . .” She also relayed the “scrutiny” she experienced during a meeting with her department: “[T]he first thing they said was, ‘Well, the girls always have trouble with physical chemistry, so you’ll take undergraduate physical chemistry.’ And I said, ‘I’m a grad student. I didn’t come here to take undergraduate courses.’”

In 1944, she and her husband, Donald Hornig, moved to Los Alamos, N.M., when he was recruited to work on the Manhattan Project as an explosives expert. She was offered a job as a typist for scientists’ reports but rejected it, suggesting she could be put to better use, given her background in chemistry. This is how Hornig is introduced in the film.

Hornig was then placed on a team of women scientists working on plutonium research. When male supervisors discovered that plutonium’s radioactivity could impact fertility, the women were reassigned. However, Hornig resisted, famously pointing out that the men were at greater risk than her—another quip that makes it into the movie.

When the scale of potential destruction became clear, Hornig was one of many Los Alamos members who signed a petition advocating that the bomb’s power be demonstrated to Japan instead of dropping it on a city.

In her 2011 interview, Hornig described the scientists’ conflicting emotions: “That was an odd mix of feelings. I mean, certainly some triumph, and the destruction was just so incredible. I think we’ve all been a little haunted by that over the years.”

Horning went on to earn her Ph.D. in chemistry from Harvard and served on the faculty at Brown University and Trinity College in Washington, D.C. In the early 1970s, she founded Higher Education Resource Services, or HERS, a nonprofit supporting women leaders in higher education. For many years, the HERS Summer Institute was held on Bryn Mawr’s campus.

Hornig persistently fought against sexism and gender inequality in academia and the sciences. She passed away in 2017 at the age of 96.

Published on: 11/15/2023