The Courage of Our Contradictions

Harris Wofford, Bryn Mawr's fifth president: 1970-1978.

In September, the College hosted a sneak preview of Harris Wofford: Slightly Mad, a new documentary about Bryn Mawr's fifth president.

On hand for the event, Elizabeth Mosier ’84 sat down with Harris Wofford for a talk about his life and times.

He marched with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., worked in the Kennedy Administration as special assistant to the president for civil rights, helped launch the Peace Corps, authored books (most notably, Of Kennedys and Kings: Making Sense of the Sixties), practiced law, served as Bryn Mawr’s second male president during the rise of the women’s movement, established and directed the Pennsylvania Governor’s Office of Citizen Service as secretary of labor and industry, started the conversation on national health care reform during his 1991 senatorial campaign (to fill Senator John Heinz’s seat after his untimely death), promoted service learning through AmeriCorps as CEO of the Corporation for National and Community Service, introduced Barack Obama before his 2008 speech on race at the National Constitution Center, and, 20 years after the death of Clare, his beloved wife of 48 years, married his late-in-life love, Matthew Charlton.

Meeting Again

For a man with such a weighty resume, Harris Llewellyn Wofford, Jr., is disarmingly light-hearted. “Over here they do everything in Welsh,” he says, laughing as he quotes a Haverford College student trying to translate his invitation to a reception at the Bryn Mawr College president’s house, where Wofford lived from 1970 to 1978. “Maybe Pen y Groes means RSVP!”

Ninety-one now, he has returned to campus for a screening of a new documentary, Harris Wofford, Slightly Mad, in which Bryn Mawr claims a middle chapter in his fascinating life story filled with plot twists. Director Jacob Finkel followed and filmed his subject for nine years, to illuminate Harris Wofford’s life and career.

At a pre-screening reception at Pen y Groes, I remind him that we’ve met before. In 1981, Wofford drove me and a few other students home from Philadelphia’s Forrest Theatre, where we’d been lucky enough to meet Katharine Hepburn after her performance in The West Side Waltz. Chatting with the alumna-actress, I mentioned that I’d drawn a dorm room at Haverford College that year. “Men and women living together!” she scolded. “I don’t approve!”

Wofford eased that sting on our way home, telling funny stories about trying to coax the icon into speaking at Commencement—a gallant effort he now recalls as “one of the great pleasures of my time at Bryn Mawr.”

(In 1973, Hepburn met with the senior class and gave an informal talk in Erdman Hall, pearls from which were reprinted in admissions publications for years to come, including: “Bryn Mawr isn’t plastic, it isn’t nylon, it’s pure gold.”)

Back then when I first met Wofford, I was a sophomore in every sense of the word. I didn’t know that the “Bi-College Cooperation” I took for granted—a deeper and stronger relationship with Haverford that included consolidated academic departments, cross-registration and majoring, and (yes, Miss Hepburn) residential exchange—was shaped by the former president’s affirmative advocacy.

As Haverford deliberated the issue of admitting women, President Wofford emphasized that cooperation between the two institutions would improve education, not merely increase coeducation. Strategically, he focused on Bryn Mawr’s strength as the only women’s college in the world with (coeducational) graduate programs and worked throughout his presidency to expand our national and international role in educating women.

Meeting Wofford again these many years later, it occurs to me that his good humor is a bridge-builder’s tool, serving as a social tie between cultures, countries, and conflicting ideas. And in all seriousness, I’m glad for the chance to thank this cheerful, big-hearted man for his steady stewardship of Bryn Mawr during a tense and pivotal time

Wofford at Bryn Mawr

President Kim Cassidy tells the audience gathered for tonight’s screening in Goodhart Hall that Wofford—whom Senator Robert Kennedy once called a “slight madman” for his compassionate commitment to civil rights—“has always been open to ideas that challenge accepted doctrines and has had the courage to speak and act for change.” She cites his trip to India with his grandmother at age 11 as the source of his fascination with Mahatma Gandhi and the anti-colonial political strategy of non-cooperation. This serendipitous event also seems to have inspired his sense of duty to cooperate with good, as his long career in government, public service, and education attests.

Bryn Mawr, with its traditions and tensions, its promise and problems, beckoned to Wofford in the spring of 1969, when Barbara Auchincloss Thacher ’40 called him on behalf of the Presidential Search Committee.

As he told the story in the 1977 Bryn Mawr Report of the President, “We were in the midst of a student sit-in (at the State University of New York’s experimental new College at Old Westbury, where he was founding president). Clare agreed to give me the message but told Mrs. Thacher she hoped that whenever we left Old Westbury her husband would go to something like a country grocery store and not to work in any college. Mrs. Thacher replied coolly, ‘Mrs. Wofford, Bryn Mawr is not any college.’ We came to learn how right she was.”

His eloquent inauguration speech reveals that he could read Bryn Mawr’s contradictions in the original Welsh: the “high hill” that offered a vital retreat from the world and that threatened intellectual and political isolation. As the new president spoke on Merion Green that day in the fall of 1970, his colleagues John F. Kennedy, Jr., Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy were gone. Distrust in government was on the rise as the Vietnam War raged on. Some students in the audience had taken fall makeup exams in spring-semester courses disrupted by anti-war protests and the Kent State shootings in May.

President Wofford’s words would have comforted some and concerned others: “American higher education stands indicted for its readiness to invent atomic bombs and do weapons research, while neglecting questions of life and death like war, poverty, discrimination, urban breakdown, over-population, and pollution,” he said. “We must find the way and the will to bring these problems from the outskirts of the Academy, where they appear mainly in extracurricular teach-ins or agitation, into the center of our study and research.”

And that’s what he set out to do. Although outwardly—architecturally—Bryn Mawr’s campus was largely unchanged in that decade dominated by the energy crisis and an economic downturn, the important interior work of reshaping our institutional identity had begun.

In an era of increasing student interest in community organization, social action, and attending law school, Wofford proposed a new master’s degree curriculum in Law and Social Policy at the Graduate School of Social Work and Social Research. Aided by the dynamic duo of Mary Patterson McPherson, Ph.D. ’69 (then undergraduate dean) and Director of Admissions Betty Vermey ’58, he increased opportunities for study and research abroad and doubled the international student presence on campus to nearly 10 percent. With “1976 Studies,” a four-year program of seminars and symposia, he connected theory and practice, “town and gown,” by bringing academic, civic, corporate, and political leaders to campus to discuss “the premises and promises of the Declaration of Independence in the light of modern American problems.” All this while fundraising for the Tenth Decade campaign, which surpassed its target to bring in $23.7 million from 1973 to 1976.

President Kim Cassidy tells the audience, “Harris has always been open to ideas that challenge accepted doctrines and has had the courage to speak and act for change.”

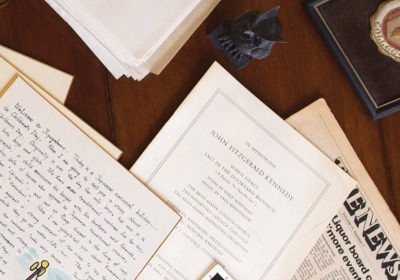

Of course, that’s not the whole story; the deeper truth is in the everyday details. In my research, I found President Wofford’s September 12, 1972, letter to Sisterhood, referencing the new Black Cultural Center at Perry House and the campus constituencies seeking the group’s input on curriculum, recruitment, career concerns, and freshman orientation. Wofford wrote to “renew the commitment of the College administration to take all steps possible to assure that the experience of Black students at Bryn Mawr is a full and good one educationally, socially, and in every way.” He copied student representatives including geologist Rhea Graham ’74, who would forge a career in environmental stewardship on her way to and from her appointment as the first woman and first African American to lead the U.S. Bureau of Mines.

As President Cassidy puts it in her introduction to Finkel’s documentary, “Harris challenged what was then a very traditional liberal arts college to bring the strength of the academy to addressing the problems of the world around us, an orientation we still have at the College today.”

Tonight, Harris Wofford is in the audience filled with his family, friends, and former colleagues, all of us eager to watch his well-lived life play on the screen.

From His Inaugural Address

"All the world is in a crisis of authority and a crisis of the intellect—of law and reason. There will be no way out unless people dare to trust their intellects in action—unless on a scale never known before reason is used with courage to right a careening world."

Published on: 12/15/2017