Perceptions of Blackness at Bryn Mawr

Scholar addresses issues of differing experiences.

To celebrate Black History Month, Bryn Mawr hosted a range of events sponsored by the NAACP, the Muslim Students Association, Sisterhood*, Art Club, and the Alumnae Association.

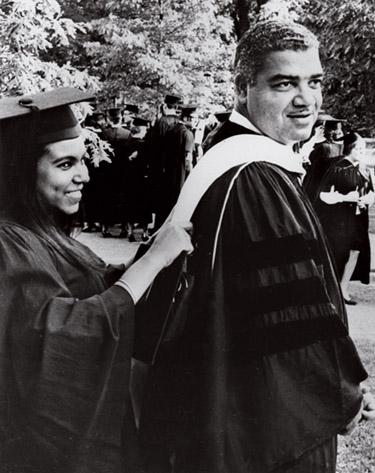

Dr. Beverly Daniel Tatum, whose book Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? has become essential reading on the dynamics of race in America, addressed a capacity crowd in Great Hall as this year’s Black History Month keynote speaker.

“I was so delighted that we were able to bring Dr. Tatum to Bryn Mawr’s campus,” says Anisha Thornabar ’19, co-president of Sisterhood*. (The asterisk denotes an inclusive community open to all genders and gender expressions.) Thornabar helped organize the event. “Her talk was amazing and engaging! She really created a great sense of community with her insightful comments on her books and views on race.”

Tatum, a clinical psychologist and emeritus president of Spelman College, was joined by Provost Mary Osirim and Jasmine Stanton ’20 for a wide-ranging discussion of race, identity and social exclusion, and higher education.

Herewith, excerpts from her remarks:

“I was doing a lot of workshops and doing a lot of speaking engagements in school districts— often school districts that were predominantly white but had a significant population of color, sometimes as the result of voluntary desegregation programs or through other means.... I’d come to those workshops to talk to those educators, and inevitably somebody would say, ‘Why are all the Black kids sitting together in the cafeteria?’

"And when they asked me that question they often asked it with the tone of voice that suggested they thought it was a problem, as in, ‘Why are they all sitting together? What can we do to make them stop or to change the dynamic so that they won’t do that anymore?’

"And what I really wanted to do in the book was to answer the question as to what draws people to sit together and to find others who have shared experiences. Sometimes it’s a shared experience of culture, it might be shared experience because they’re living in the same neighborhood; it might be shared experience because they are dealing with issues of racism in the school. There are lots of ways people have shared experiences, but the fact of the matter is we all seek the comfort of the familiar, and there’s nothing wrong with that. In the context of an educational environment like Bryn Mawr, or those schools that I was in, I used to say let’s worry less about who’s sitting with who at lunch and think about what’s happening in classrooms.

"We know that in 1950 the U.S. population was 90 percent white. In 2014, the school-age population was more than 50 percent children of color. That’s a big change, and that change has taken place not just in the past 20 years, but certainly it has accelerated over the past 20 years—a consequence of both immigration as well as differential birth rates. Yet, while that’s a big change, we know that some of the old patterns of the past are still in place.

"For example, neighborhoods continue to be very segregated in the United States. And because we have walked away from, or moved away from, some of the strategies we’ve used to desegregate schools, schools today are actually more segregated than they were 20 years ago. That means that in 2018 we have a situation where lots of young people are coming into colleges and universities that have become more diverse in terms of the student population, but students arrive with very limited experience in engaging [across difference] with each other prior to getting to college. So, there is a kind of opportunity that higher education offers that I wanted to write about, but there’s also a challenge in that the kinds of misinformation that were part of segregated environments 20, 30, 40 years ago are still part of today’s socialization. And many students bring that misinformation and those stereotypes into the interactions they have on campus.”

"There’s value, of course, in cultivating a collective voice, but one of the things that I have seen happen is sometimes assuming that there is a single voice, or a single experience. And so, I think it's really important to recognize—and this is one of the values of coming to an environment and really learning about other people’s experiences—that often whatever your experience is, people enter into spaces and think their experience is the universal experience, right? ... I had a friend at Wesleyan. When I first met her, we became very good friends. She was African-American, I’m African-American, but we had very different life experiences. She grew up in the South Bronx. I grew up in Bridgewater, Massachusetts—you can’t get much different than that. But one of the things she told me was, “Until I came here, I thought all Black people were poor” because every Black person she knew in her neighborhood was poor. I had a different experience. I grew up in a solidly middle-class family, in this predominantly White town. My mom was a schoolteacher, and my dad was a college professor—very different life experiences. But my experience was also a Black experience.And so part of the challenge that we have to understand is that people come from different places and have different experiences, but race can still impact that experience. It doesn’t necessarily play itself out in the same way for each person. A collective voice is like a choir. When you are singing in a choir, you’re not all singing the same note. There’s a kind of harmony that can happen. And so you need to learn what your own voice is, whether you’re an alto or a soprano; recognize that we each have our own stories; and learn how those stories come together in a way that allows us to sing collectively about our shared experiences. That's the challenge.”

"One of the things that I will say about the 2017 version of my book versus the 1997 version that people may have already noticed, if you’re familiar with the earlier version, is that the new version is about 150 pages longer. And one of the reasons it’s longer is because it seemed to me that there were some things that people needed to understand from a historical perspective about which many people did not have accurate information, not because it’s not available. It’s just that we don’t learn about it in school—it’s not talked about much. And I think it’s very difficult to understand our current moment without historical context. That is why I put more history in this version of my book than in the earlier version. But as much as there is, there’s much more that there could be, so I really think it’s one of the challenges we have as a nation that we don’t spend enough time really understanding our past, because it lays the foundation for what we’re experiencing in the present.”

"There are lots of campuses where the effort to have dialogue—what is being described as dialogue—is really more like a two-hour workshop, and the problem with short interventions is that it usually is just enough to generate discomfort. If you generate discomfort, people will say ‘that was uncomfortable; I don't want to do that anymore.’ Right? One of the values of having a longer time is that there's a certain arc of discomfort, right? So let’s imagine I’m drawing this arc with my hands. You know, if you just do the first part, you stop at the top when people are most uncomfortable, and you don’t get through that point. ... But if you stick with it—even when it’s uncomfortable—eventually you get to the part that’s fun, which is when people really start to feel, gosh, I am understanding this, and I’m making relationships with people I wouldn’t otherwise have had relationships with, and I’m feeling a kind of sense of possibility in terms of what I can do in my own sphere of influence. And that’s quite liberating.”

Published on: 05/14/2018