Woman to Woman

Journalist Barbara Kevles ’62 reflects on her interviews with some of the most important women in American culture.

In the 1990s, Bryn Mawr Libraries acquired recordings and research materials from journalist and author Barbara Kevles ’62. Kevles, whose journalistic work is also in the collections of Yale University Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, and Stanford University Libraries Special Collections, has worked as a freelance journalist for major publications for over 50 years. Her articles have been published in such national magazines as Esquire, Salon, The Atlantic, The New York Times, The Paris Review, People, Harper’s Bazaar, Cosmopolitan, Glamour, Redbook, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Good Housekeeping.

She interviewed some of the most important women in American culture from the late 1960s through the 1970s. The materials purchased by the College, known as the Barbara Lynne Kevles Papers and Recordings, include almost 40 interview tapes featuring winners of Oscars, Emmys, and Grammys, the first Black champion of Wimbledon, pioneer politicians, an international diplomat, and more. Her memories of some of these interviews and their meaning to Kevles follow.

Jeanne Moreau

I was supposed to interview leading French actress Jeanne Moreau for the Working Woman charter issue in New York. But she bailed from the flu and then decamped to the Beverly Hills home of her husband-to-be, director William Friedkin. When we finally met, she asked, “Why did you follow me?”

I blurted out that important creative women I’d interviewed like Pulitzer poet Anne Sexton and photographer Diane Arbus had killed themselves. Toward the end, Moreau gave me what I was seeking. Lighting a cigarette, she said, “The choices I made, the energy, the depressions ... all of that is constructive. … When … you’re facing a wall, what’s really reassuring is … nothing lasts in life. Not even despair. Not even happiness. It will be changed into something else. … So that’s renewing.”

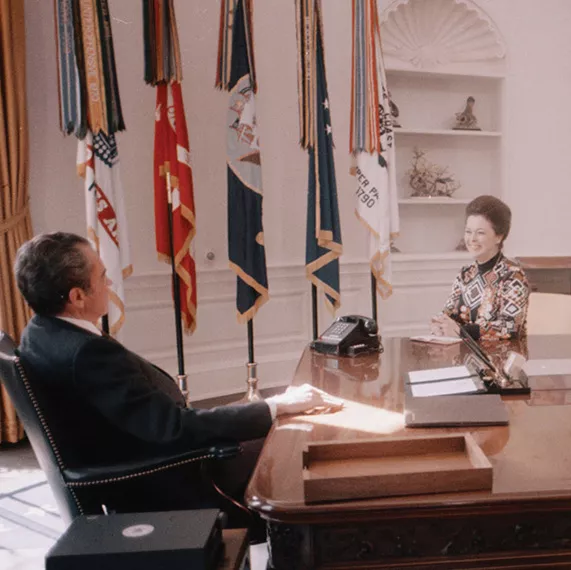

Joan Kennedy

“How would you like to be known just as a sexy blond,” Joan Kennedy asked during a watershed interview for a 1969 Good Housekeeping cover story. The press had roasted her for wearing a silver mini-dress to a President Nixon White House afternoon reception.

The dumb blond moniker hardly described Senator Ted Kennedy’s wife. In 1964, she did what no other Kennedy woman had done—campaigned successfully for re-election in place of her husband, who was immobilized from a severe back injury suffered in a plane crash. In 1967, Washington’s National Symphony Orchestra invited this Manhattanville College music major to narrate Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, a feat she repeated with conductor Arthur Fiedler in Boston and Tanglewood. Kennedy told me, “I’d rather help Ted in this way than campaign.”

Edith Head

Hollywood costume designer Edith Head, a Working Woman assignment, took no chances on the first day of filming Universal’s multimillion-dollar Airport '77. The eight-time Oscar winner had arrived at 7 that morning to be sure she had doubles, triples, quadruples of all accessories. Because of casting problems, many costumes were on the set for the first time. She said, “What tries the nerves is worrying whether they will photograph right.”

She added, “I’m under terrific pressures. I’m under such pressures that at the drop of a hat, I’d crash through the ceiling if I could.”

Eunice Kennedy Shriver

Eunice Kennedy Shriver, featured in a March '76 Ladies’ Home Journal profile, was shameless when it came to getting something she wanted done. She called congressmen and senators in the morning between 6 and 8. She once called her youngest brother, Senator Ted Kennedy, at 5:40 a.m. “Eunice, I’m sleeping,” he protested. “But you’re awake now,” she said, and continued.

Her singular “calling” was for the intellectually impaired. One night she asked her older brother, President John Kennedy, if he would be willing to appoint a presidential panel to study the problems and needs of the intellectually impaired. “Is a panel necessary?” he asked. She reminded him that in a recent congressional report on mental health “the retarded aren’t even mentioned.”

The resulting 1961 President's Panel on Mental Retardation, on which Shriver served as unpaid consultant, led to passage of the Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act, signed into law three weeks before her brother’s assassination. An associate told me: “Eunice’s the nearest thing to JFK when it comes to political instincts. She’s not one … who likes to claim credit, but … she’s the one who got that mental retardation law passed.”

Shirley Temple Black

At 43, Mrs. Charles Black still possessed the Shirley Temple pout and squiggle of dimples of her famous childhood. We met for lunch at New York’s Waldorf Astoria for a Saturday Evening Post feature about Black’s new role as deputy chairman of the U.S. Delegation to the U.N. Preparatory Committee for the first U.N Conference on the Human Environment.

A waiter brought a specialty—compliments of the house—to Little Miss Marker. “Why didn’t you become the spoiled child of your generation?” I asked.

She laughed, “I started working at age 3 and at that age it seemed very natural—like, ‘Doesn’t everybody make movies?’ I didn’t know any different.”

The studio stress on discipline and preparation helped her excel as a diplomat. Ambassador Glenn Olds, then number two at the mission and later president of Kent State University, dubbed Black “The U.S.’ secret weapon.” Her popularity and glamour as a former movie star helped. “People were surprised by the

toughness of her positions,” Olds argued, “but she prepared. That’s what made her tough-minded.”

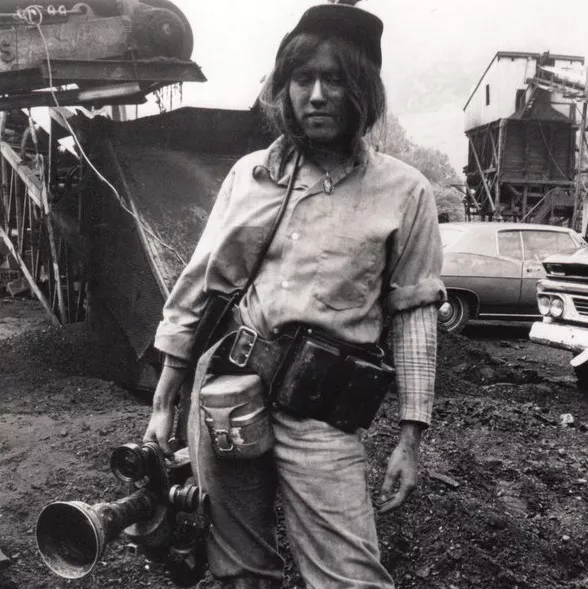

Barbara Kopple

I interviewed director Barbara Kopple, then 30, a month after Harlan County, USA, a film about a miners’ strike, won a coveted Academy Award for Best Documentary. I lobbed many questions including how she handled discrimination as a woman in the Kentucky coal fields. She told about filming the last week of the trial of United Mine Workers of America President Tony Boyle. He faced charges of conspiracy in the murder of a UMWA opponent, his wife,

and their daughter.

A CBS network cameraman insisted she get press credentials. She had—from UPI—but he called and demanded they be revoked. She replaced them with top security American Film Institute grantee credentials and was back the next morning. “He was livid. He was outside with other network camera people character assassinating us,” Kopple said. “It was the day of the verdict so we were set up inside.” When they wheeled Boyle out, he recognized her, answered some questions, and left. “The network camera people had blown the whole thing,” she said.

“Suddenly, I felt this guy ripping the microphone out of my hand and yelling, ‘I’m going to kill you.’” Kopple shot back with, “Think about what you’re doing because you’re being filmed.” He backed off.

“It wasn’t necessary to get angry,” Kopple stressed. “It was necessary to … figure out how to get around that … to do what I wanted to do.” Kopple was awarded the first of two Oscars on March 28, 1977.

Copyright © 2022 by Barbara L. Kevles. All Rights Reserved.

Published on: 10/26/2022