The Vision Behind a Timeless Campus

How the original Olmsted plan for the campus has endured through the years.

When Bryn Mawr’s founders began contemplating the layout of the College in the 1870s they thought about not just the buildings but also the grounds. The first landscape architect to design a plan for the campus was Calvert Vaux, one half of the design team behind Manhattan’s Central Park. Vaux outlined a vision that featured a central square of green space around which buildings would be situated, not dissimilar to Merion Green today. The perimeter would be densely packed with trees and other plantings. The campus would be accessible through a handful of grand entrances, following curved roads to the center, which, helpfully, would obscure buildings from view when visitors first approached the College, creating the illusion of entering a hidden world.

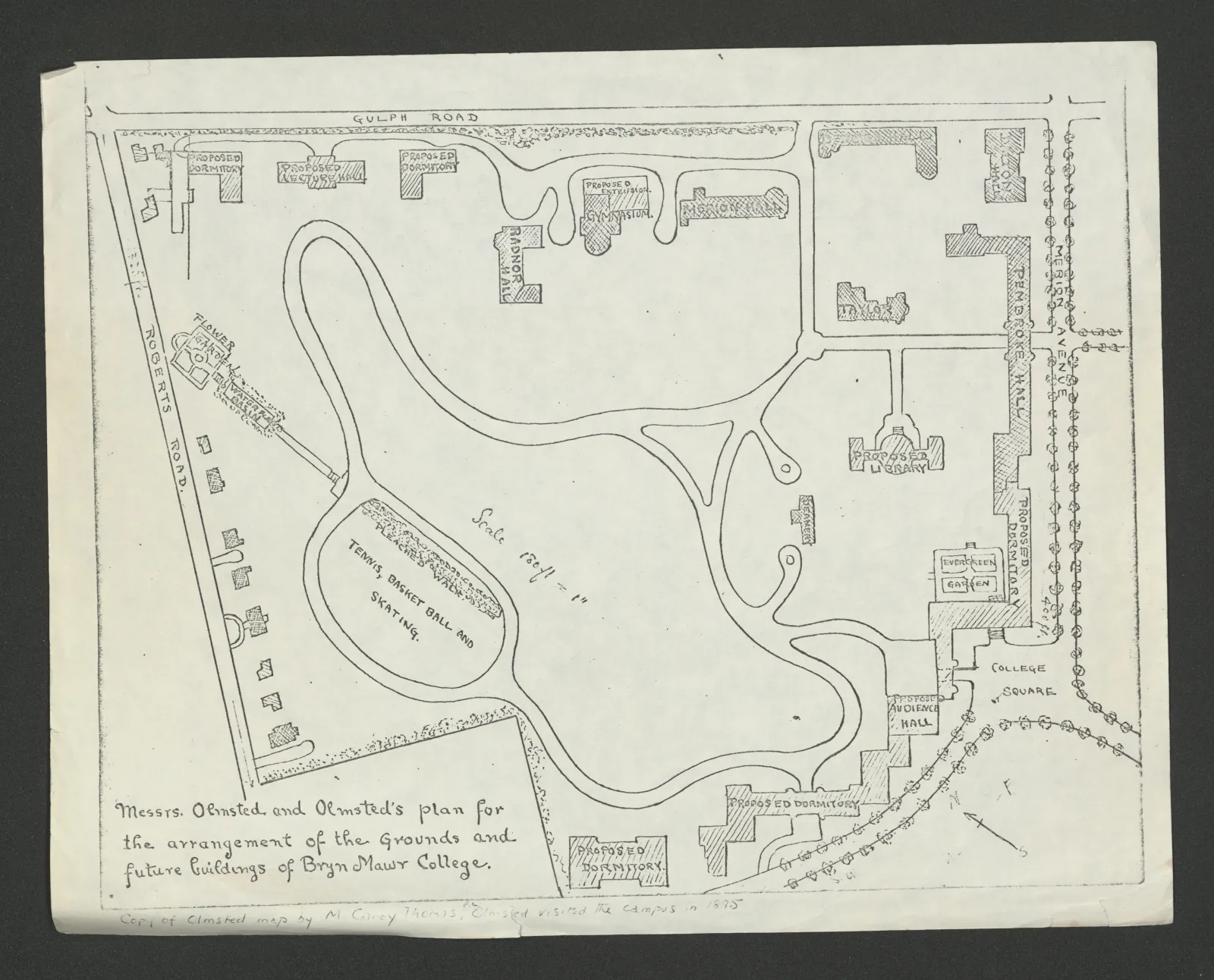

Vaux’s plan, however, was short-lived. It was designed with the College’s original 32-acre footprint in mind, but by 1895, the College had acquired more land, and its student body was expanding. At the behest of newly appointed College president M. Carey Thomas, the College contracted with Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. and his sons, John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., to update the campus plan. Vaux had died earlier that year, and Olmsted—his former business partner and the other half of the design team behind Central Park—was a logical successor.

Unlike Vaux, who was an architect, Olmsted had no formal training in design. He came to landscape architecture through a hobbyist farm and his admiration of the green spaces he saw on a visit to England, especially Birkenhead Park. Birkenhead, in Liverpool, is considered the world’s first real public park, created in a period when industrialization was at its peak and most green space was privately owned.

Olmsted saw both the aesthetic and social value of public parks and became their champion. His passion for parks led to Olmsted becoming part of the early conservation movement in the United States, playing an important role in efforts to designate Yosemite Valley as a public reserve and prevent the construction of hydroelectric power plants on Niagara Falls. Olmsted passed his skills and passion down to his sons, who followed in his footsteps, becoming landscape architects themselves.

The Olmsteds’ love of green space is evident in their plan for the College, which echoes the quasi-natural, romantic style of landscaping that Olmsted Sr. first observed in England. You can still see the shape of their planning in the campus’ present layout. Their combination field/skating rink, for example, is now Applebee Field; the curvilinear pathways first proposed by Vaux are likewise still extant, following the slopes of Bryn Mawr’s grounds.

In the shade of Senior Row and the quiet of Taft Garden, Olmsted’s enduring designs show that although the needs of the campus have changed over time, the desire for a peaceful place to sit outside remains.

Published on: 06/06/2025