History of Art's Michelle Smiley researches the development of photography in antebellum Philadelphia

Year-long fellowship allows History of Art's Michelle Smiley to explore the history and development of photography in antebellum America.

Over the past 25 years, art historians have been working to rewrite the early history and development of photography. Now, instead of reading only of Louis Daguerre’s eponymous invention in 1839, the daguerreotype, one encounters a number of contemporaneous stories about inventors, artists, and chemists working on a range of methods and techniques for capturing and fixing images.

For Michelle Smiley (Ph.D. candidate, M.A. ‘15 B.A. ‘12), some of the most intriguing developments in the medium were happening in the city of Philadelphia in the years leading up to and immediately following the announcement of Daguerre’s invention.

As the recipient of a year-long Dissertation Fellowship from the Consortium for the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine, Michelle has been able to spend the last several months diving into area archives and learn about a number of important Philadelphians whose experiments and discoveries directly impacted how photography developed in the U.S.

One such figure was Joseph Saxton, an inventor who worked at the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia during the time of Daguerre’s announcement. Using materials readily at hand at the Mint, Saxton was able to try out Daguerre’s method soon after it was made public. By coating a blank coin form in silver nitrate, Saxton successfully made an image of the Philadelphia Central High School, now the oldest surviving photograph in the U.S.

In addition to Saxton, Philadelphia was home to a thriving community of chemists and instrument makers who soon discovered ways to improve on the new technology. As Michelle explains, “Philadelphia offered the best scientific training at the time. At the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, chemistry was not yet its own discipline; that work was being done in medical colleges and Philadelphia had the first medical college in the country."

One of the earliest advancements in American photography came from Paul Beck Goddard, a medical doctor and chemist. In the fall of 1839, Goddard discovered that bromide could be used to dramatically accelerate the photographic process. "It was figures like Goddard that made Philadelphia a center for photographic development,” Michelle explains. “There were a number of chemists and scientists and instrument makers who had the technical knowledge to rapidly improve on the daguerreotype process, once it was released in January of 1839."

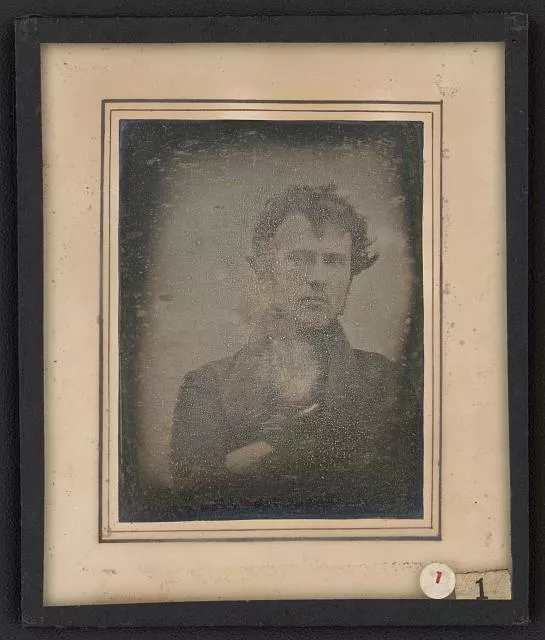

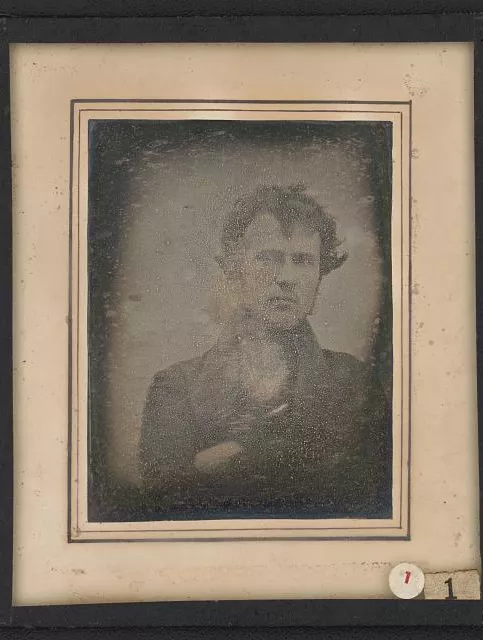

While similar discoveries were occurring simultaneously across the globe, many of these ideas did not circulate beyond their local communities until many years later. Michelle notes that the photographic scene in America was marked by a sense of collaboration, which helped spur developments in the medium. For example, Goddard teamed up with the metallurgist Robert Cornelius, who came up with a technique to improve the smoothness of the photographic plate, yielding sharper photographic images.

By speeding up the exposure time and improving the image quality, American innovations opened new commercial opportunities for the medium. According to Michelle, "a burgeoning middle class that wanted self-representations created a market for daguerreotypy in Philadelphia, which was answered by a number of entrepreneurs from the city’s rising merchant class." And indeed, in the winter of 1840 Goddard and Cornelius opened the world's first photographic studio in Philadelphia.

As a Dissertation Fellow, Michelle has had access to a number of archives in the Philadelphia region, many of which are also supporting members of the Consortium. She has looked at the memoirs and scientific papers of many key figures, housed in such institutions as the American Philosophical Society, UPenn, and the Library Company, and viewed some of the earliest photographic instruments at the Smithsonian Institute.

In her dissertation, Michelle will explore the long history of photography in the U.S., from its earliest days to the present, but her focus is primarily on the impact technological improvements have had on the development of the medium. Her fellowship from the Consortium for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine has therefore provided crucial access to a broader community of scholars with technical expertise beyond the field of art history.

Michelle, whose interest in early photography initially led her to the field of history of science, has benefited from this collaborative academic environment. Consortium fellows meet regularly to discuss their research and participate in working groups. "I've discovered that they have different commitments than your typical art historian. They're interested in who made certain discoveries, what were their working practices, who did they study under, what are the mechanics of the invention. The history of science really gets into the nitty-gritty."

Immersed in this environment, Michelle hopes to bring a new perspective to the early history of photography not typically found in art historical accounts. "Photography has always been talked about as both an art and a science, but the early history of photography was full of technological developments,” she says. “I was interested in what the history of science could add to the more art historical approaches."

At the same time, Michelle has discovered similarities among the two approaches, especially the desire to situate discoveries within larger socio-economic and political contexts. And Michelle has also brought to the group her careful attention to images, asking her peers to consider how the representation of scientific discoveries and inventors is indebted to a longer history of visual motifs—like the many portraits of scientists modeled on tropes of the artist-genius toiling away in solitude.

Though Michelle's fellowship is drawing to a close, she plans to stay involved with the Consortium by continuing to participate in its working groups, which have always been open to the public. This summer she will be re-working her most recent dissertation chapter for publication; it focuses on the many intersections between early photography and the U.S. Mint which she has uncovered during her year of archival research.