“This both is and is not an origin story.” says Michelle Smiley, Ph.D. Candidate in History of Art. Michelle’s research casts the early days of photography in a new light, bringing voice to forgotten figures in the development of the medium. “The idea of photography’s origin story is a misnomer. The medium was constantly being reinvented by all different kinds of people – engineers, artists, chemists.”

In the early 19th century, Philadelphia’s scientific community was the crux of American technological innovation. Michelle has found that the city’s antebellum scientific community played a major role in establishing photography as a new medium. It is this work that has brought Michelle halfway through her two-year Andrew Wyeth Fellowship at the Center for Advance Study and Visual Arts (CASVA) in Washington, D.C.

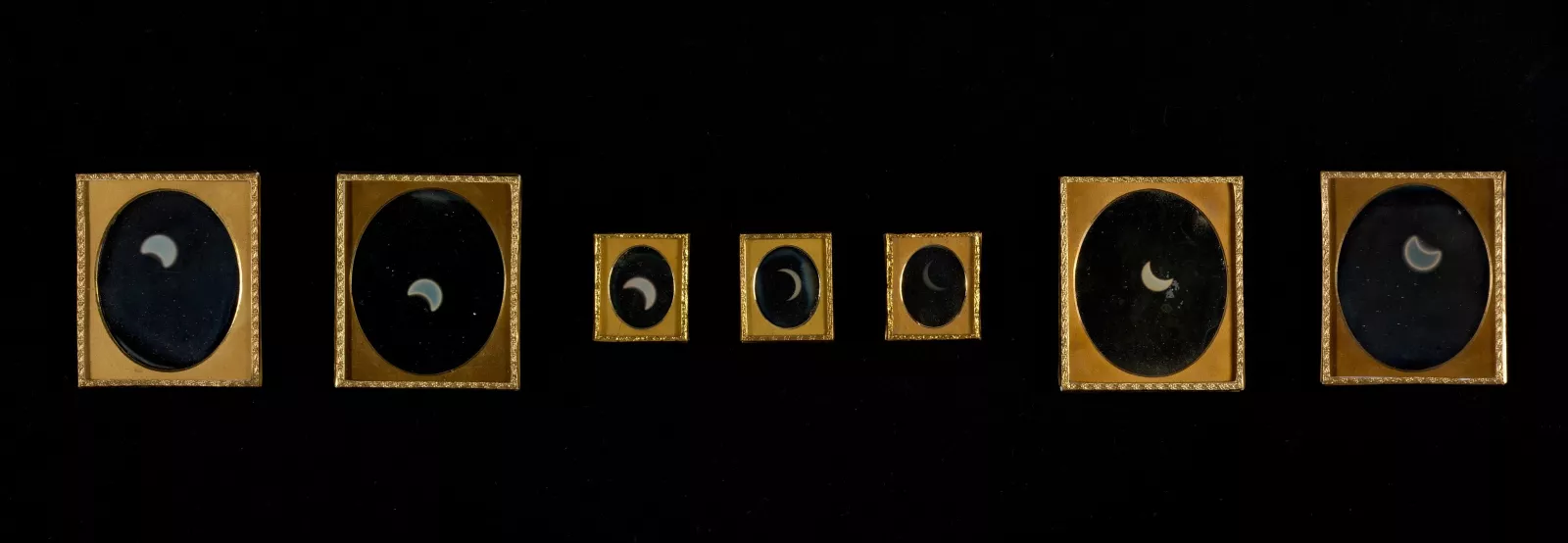

As a Wyeth fellow, Michelle is de-centering traditionally held wisdom of the history of photography – a narrative that establishes photography’s origin in Europe as the distinct inventions of William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-77) and Louis Daguerre (1787-1851). Talbot’s calotype and the Daguerre’s daguerreotype are photographic processes that historians look to as evidence for photography’s development as a series of singular inventions.

Michelle has found that the notion of distinct, ex novo invention is inappropriate to describe the photography’s early days. In Philadelphia, new technologies that would eventually lend themselves to the photographic process were developing in a series of fits and starts, as part of an interactive community of engaged experimenters. Technological developments in areas such as light capture or the chemical processes necessary to produce a still image were emerging from the city’s nascent scientific community. The processes developed by Talbot and Daguerre were themselves in conversation with - and inspired by - a trans-Atlantic network of ideas that link Europe to communities of early scientific practitioners in America.

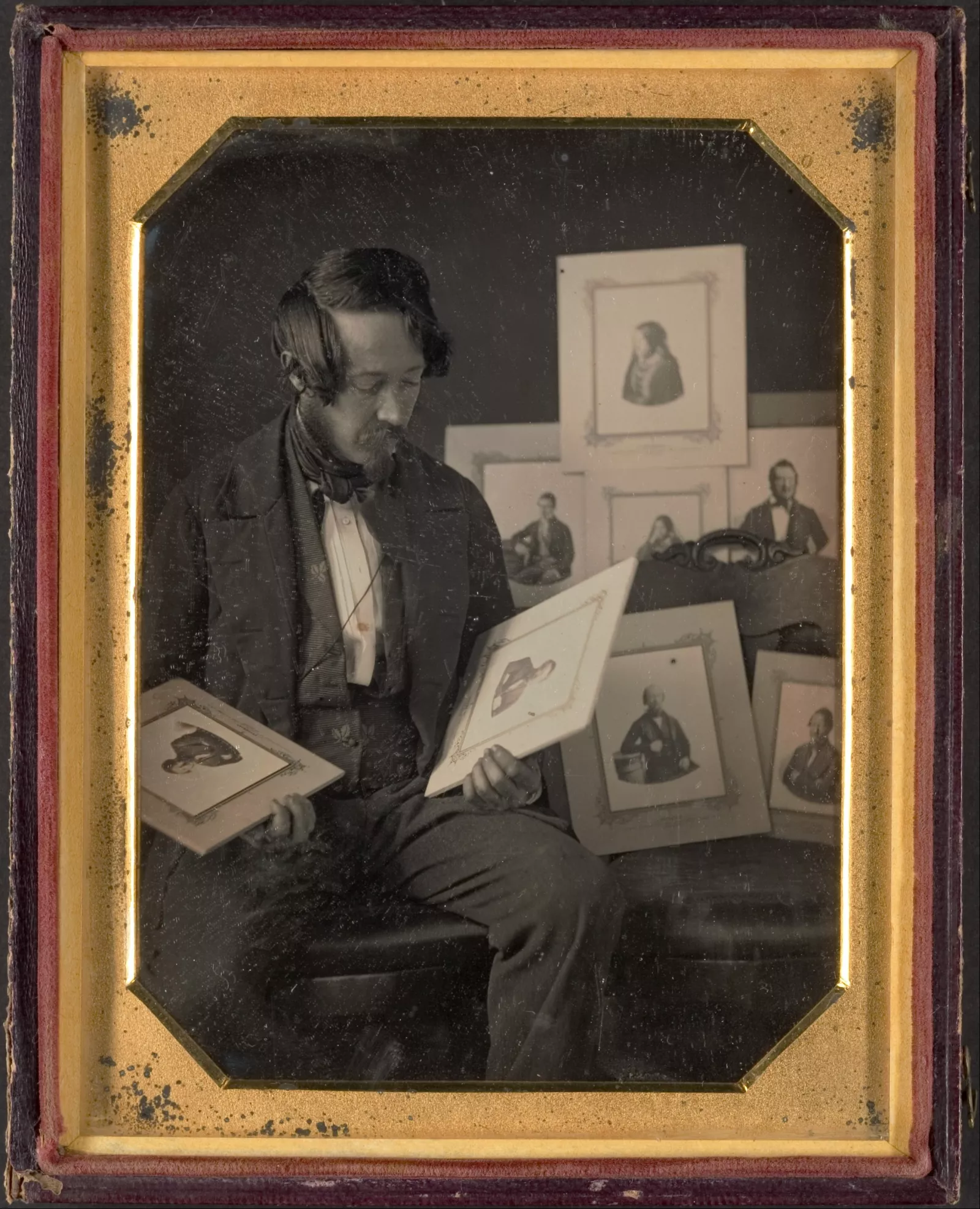

Medical students and doctors, brewers, homemakers, engineers – these were Philadelphia’s leaders in science before the natural sciences were crystallized into formal academic disciplines in the United States. As Michelle notes, many of these individuals were “not necessarily doing photographic things per se, but whose curiosity and experimental work developed techniques that that would contribute to the development of photography later on.”

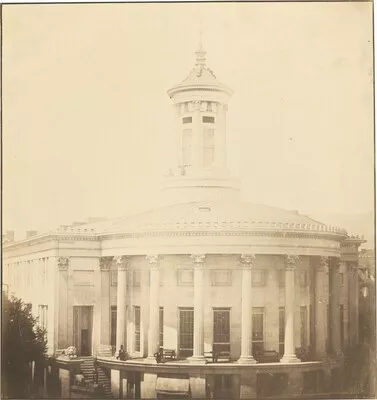

What was it about Philadelphia that fostered the growth of American science? Michelle thinks this has to do with the fact that Philadelphia had the earliest medical school in America. Founded in 1765, the College of Philadelphia was one of the only institutions in America with the means to provide a formal scientific education in fields such as chemistry and anatomy. The school would later become today’s University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

While this speaks to an elite scientific community, Philadelphia’s broader vernacular scientific community was encouraged by the help of the American Philosophical Society. The very mission of the society was to “circulate useful knowledge about infrastructure and knowledge about what was useful in the land that was actively being stolen from indigenous communities who lived here.”

Michelle has found that Antebellum photographic methods developed from a public interest in the methods of natural history - documenting surface appearances of observed phenomena and the processes that enable them. With the institutionalization of science, Michelle finds a paradigm shift in thinking about captured still images – a new desire to know what is behind these surfaces. Invisible wavelengths of the light spectrum were discovered and a recognition of natural phenomena that are beyond human sight. “From this develops technical apparatuses like the photograph, which was utilized to picture things that are invisible to the human eye. So they're looking for the deeper root of the causes of the physical world versus categorizing the visible world.”

This means that Michelle’s dissertation has taken unexpected turns. In many respects her work is as much about the history of scientific practice in America as much as it is about photography. When she began her research, she was confronted by a field of the History of Science in America that was (and still is) in its infant stages. Her challenge then was constructing a rough narrative of the development of science to understand the ways in which photographic techniques developed out of them.

Her project has since developed into a true exercise in the spirit of interdisciplinary research acquired as a graduate student in Bryn Mawr’s History of Art Program, and likewise as a Wyeth Fellow at the Center for Advance Study and Visual Arts. At CASVA Michelle is part of a small Art History community of seven other Ph.D. students, in addition to a number of postdoctoral and senior fellows. Housed inside the National Gallery, CASVA offers its fellows a unique interdisciplinary experience where each fellow act as a representative of their own sub-discipline – for Michelle, American photography. Be it through weekly student lectures, or discussion sessions, Michelle is part of a community in constant communication led by Bryn Mawr Alum Elizabeth Cropper (Ph.D. History of Art, ‘72), Dean of CASVA.